What's the difference between a "cult" and a "new religious movement?"

Why do devotees follow people like Da Free John, a.k.a Adi Da? Meanwhile, a noted scholar of new religious movements suggests that this guru's messianic truth claims may actually be true.

Most people who join sects, cults and new religious movements are sincere ideological converts. They’re spiritual seekers looking for new ways to bring more meaning and belonging into their lives, just like those who join more mainstream churches and other religious congregations. Today, many scholars and perhaps most religion reporters shy away from even using the word “cult,” citing its derogatory connotations. I get it, but it’s a word I refuse to retire.

All religions start as cults or sects. To me, a cult is a group that shows an usual degree of devotion to its leader or its philosophical or political ideas. Technically speaking, sects are splinter groups that grow out of other religious movements. Christianity began as a Jewish sect. Today, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, founded in the 19th century by the American Mormon prophet Joseph Smith, is considered to be a major world religion, but it was long seen as our nation’s most notorious, dangerous cult. In the Roman Catholic Church, those who show an extraordinary reverence to the mother of Jesus are sometimes described as being in “the cult of Mary.” Some even used that term to describe the faith of the late Polish pontiff, Pope John Paul II.

So, in my view, we can righteously describe the followers of Franklin Albert Jones as spiritual seekers, cultists or sectarians. His church, after all, did originally split off from the Siddha Yoga movement of the Indian guru Swami Muktananda. Yes, there were credible reports of sexual abuse by both Swami Muktananda and Da Free John, just like there are of Roman Catholic priests and Southern Baptist pastors. Newspaper reporters, myself included, love stories about sex-crazed gurus and hypocritical priests and pastors caught with their pants down. Sex and sensationalism sell newspapers, or as an Examiner editor once advised, “put the fucking in the lede.” It’s the same old story in today’s ubiquitous online world, where sex and sensationalism serve as enticing clickbait.

In the cult wars of the 1970s and 1980s, scholarly experts and self-appointed pundits fell into two camps — the apologists and the alarmists. The apologists were often the academic defenders of controversial new religious movements. They were more interested in what these emerging spiritual organizations believe and how that fits into the broader tapestry of the world’s religions. The alarmists focused on the actions of cult leaders, especially when they appeared to be exploiting or abusing their followers. In my journalistic work, I’ve tried to take a middle path, talking to both sides and hoping that truth lies somewhere between the alarm bells and the apologia.

So, in the case of Da Free John, defectors and dissidents like Sal Lucania, the guru’s original front man, stress the importance of judging the guru’s actions, not his writings. “What he does and what he says have absolutely, literally, nothing to do with each other. That’s the whole issue. That’s the crux of the fraud,” Lucania told me upon my return from Fiji. “You don’t talk the talk unless you walk the walk. Otherwise, it’s just bullshit. People are putting their lives in this man’s hands. He’s dangerous, and he needs to be stopped.”

Professor Jeffrey Kripal, a noted religion scholar at Rice University, takes a radically different view. In Da Free John, he sees “a man whose life and teachings display in abundance the charismatic energies, miracle stories, philosophical complexities, and ethical controversies” of the modern guru. His American birth makes him particularly interesting, as does “the quite public fashion in which they have handled the question of sexuality and its central role in the spiritual life of the community.”

Here, Kripal writes, is a guru whose “daughters and his two partners are not only present but ritually privileged” in his religious rituals

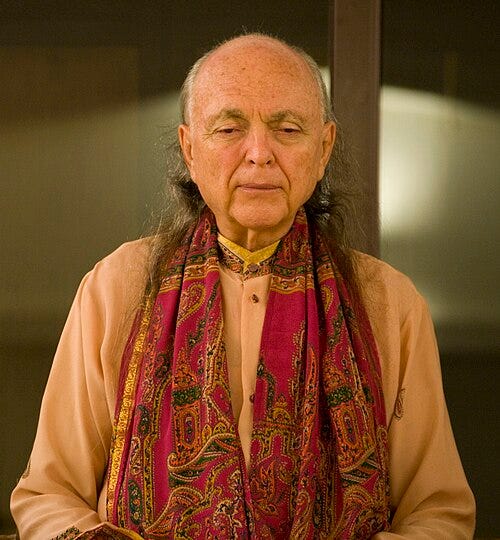

Franklin Albert Jones, aka Da Free John and Adi Da Samraj, pictured in 2008.

In an essay titled “Riding the Dawn Horse — Adi Da and the Eros of Nonduality,” Kripal does a masterful job at summarizing Da Free John’s paradoxical "crazy wisdom” mix of non-dual Vedanta, Japanese Zen and Tibetan Buddhism. “Nothing can be done to effect that pristine state of consciousness that already is and yet something must be done in order that it may appear in the phenomenal experience of the aspirant — the path that is not a path.” Kripal is so impressed with this guru’s East-meets-West synthesis that he says Da Free John may be “the inevitable end and fulfillment of the radical nondual logic.”

In this sense at least, Kripal writes, the guru is “entirely justified in his claims: He does indeed literally fulfill the promise of the Indian nondual traditions for the West.”

Kripal notes that various Indian gurus “have become the object of serious and convincing ethical critiques, almost always involving their secret sexualities and false fronts of celibacy.” Da Free John and associates “employ antinomian shock tactics that appear to be immoral or abusive in order to push his disciples into new forms of awareness and freedom,” but they did not claim to be celibate.

“Perhaps what is most remarkable about the case of [Da Free John] is the simple fact that the community has never denied the most basic substance of the charges, that is, that sexual experimentation was indeed used in the ashrams and that some people experienced this as abusive.”

In the “crazy wisdom” tradition, Kripal writes, “there is nothing contradictory about individuals having profound religious experiences with ‘immoral gurus.’ ”

“Indeed, I would go so far as to say that no fallacy has done more damage to the critical study and public understanding of gurus (or mysticism in general) than the historically and psychologically groundless notion that profound and positive mystical states imply or require some sort of moral perfection or social rectitude on the part of the teacher.”

Da Free John and his following survived the sudden wave of unwanted media attention they received in 1985. Lawsuits filed on both sides were settled out of court for undisclosed payouts. After a couple more name changes, the man born Franklin Albert Jones died on Naitauba on November 27, 2008. He was known then and now as Adi Da. His religious organization, Adidam, survived his death and continues to attract new followers. The ashrams in Fiji, Kauai and Lake County remain open for meditation retreats and posthumous devotion.

Over the years, I’ve privately recounted the inside story of my Fijian adventure more than a few times, mostly to other journalists at booze-soaked gatherings where we’d trot out the old war stories — some involving actual wars, not just my “cult wars.” The most recent re-tellings of this guru saga were with a couple folks who made me realize that perhaps I need to dig a bit deeper to understand the meaning beyond this messianic madness.

Seattle attorney John Rapp had more than a passing interest in the tale. He’d floated in and out of the Free John/Adi Da orbit over the past three decades, both during the guru’s life and after his passing. Back in the 1990s, he told me, there were discussions about him possibly becoming general counsel, or maybe even CEO.

Our paths crossed in more recent years when I briefly joined an emerging “entheogenic” church while reporting for my most recent book, God on Psychedelics — Tripping Across the Rubble of Old-time Religion. Rapp, who has done legal work for the cannabis and psychedelic drug reform movement, was also a member of Sacred Garden Church, which at the time had congregations in Oakland and Seattle.

John Rapp first encountered Da Free John in the 1980s through his books and at events at the Seattle branch of Dawn Horse Books, run by devotees. At the time, the Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh was attracting a lot more attention in the news media and among spiritual seekers. Rapp found himself “going down the Rajneesh path for a few years,” then reconnecting with the Adi Da movement in the 1990s. “Rajneesh was just partying all the time, but Adi Da had all these really creative, high-powered people around him.”

Adi Da encouraged serious study of the world’s religions. Rajneesh just asked you to wear a necklace with his picture dangling at the end. Rapp spent two weeks at the Fiji retreat and made numerous pilgrimages to the Lake County ashram, sitting at the feet of the master. “There was just something about his presence,” John told me. “It was a whole emotional thing. You felt alive and present, a bit like being stoned. When he was living at the Lake County ashram, I’d start feeling this spiritual energy when I was driving up there, miles away from the place.”

Rapp grew up in a devout Christian family, and always wondered whether another messiah would appear in his lifetime. “What would another Jesus look like? Despite all his flaws, you had a bit of that feeling around Adi Da.”

Perhaps this is why Jeffrey Kripal asked me to consider the possibility that Free John actually is the messiah. Perhaps his devotees are speaking the truth when they say Franklin Alpert Jones is the “the promised God-Man” and “the most miraculous Being Who has ever lived.” In an hour-long Zoom conversation, Kripal offered a sharp critique of the way popular culture and the news media depict “cults,” a term he suggested I avoid. After reviewing a few of my stories about Da Free John from 1985, he suggested that I expand my sense of the possible.

“What I don’t see in the media’s depiction of ‘cults’ is any recognition that maybe deification is a real thing,” he said. “Maybe people actually do experience themselves as God. If we accept that, then what follows? A lot follows, including spiritual movements like this. To me, the real misunderstanding is our secular culture’s complete ignorance around the sacred, around mystical experience.”

Kripal first read some of Da Free John’s books in the 1980s and was amazed. He agreed with Alan Watts’ scholarly embrace of Free John’s work back in the early 1970s. “This is the real deal,” Jeff thought. “This is what radical non-duality looks like.” Then one day, in the mid-1990s, Kripal was sitting at his desk at Westminster College when he got a call from one of Free John’s senior disciples, who told him “we flew your dissertation out to Fiji and our guru is teaching it.”

Kripal’s dissertation, published in book form as Kali’s Child, was a radical reappraisal of the life and teachings the influential 19th century Indian guru Swami Ramakrishna. The crucially acclaimed book ignited a firestorm of controversy in India because of Kripal’s discussion of homoerotic themes in some of Ramakrishna’s secret writings. “It turns out,” Kripal said, “that Adi Da was a big fan of Kali’s Child.”

In late 1998, he visited the Lake County ashram and sat in silent darshan with the guru. That’s the only time he ever “met” him. While they never spoke, Kripal had a long correspondence with Adi Da and agreed to write a laudatory foreword to a new edition of the guru’s autobiography, Knee of Listening. Kripal never considered himself a devotee, more of an academic admirer. But he has had lots of conversations over the years with followers of gurus like Adi Da and Swami Muktananda, and he believes the powerful experiences many devotees have in their presence are real and profound.

In my view, these experience are real to the person experiencing them. But I tend to explain these see these states as sociological or psychological creations. These followers are swept up in rituals and carefully crafted environments that create the thrall of devotion. Jeff calls that theory “too reductive.”

“I think there is something very real and important and profound about the presence of those charismatic persons,” he said. “Muktananda was radioactive. He would touch people and just send them into the stratosphere. He had real shaktipat. He was the real deal, too. But I don’t associate that with any morality. It’s like putting your finger in a light socket. It’s going to shock the hell out of you regardless of your moral status or your moral behavior. I’ve had other friends who got nothing from Muktananda and were just creeped out by him. The response to the guru is very individual.”

Neither Kripal nor I appear to be the type of person who can easily tap into the paranormal powers of a charismatic guru — or even desire to open up in that fashion. “One’s filter can be very thick, or it can be very porous. Mine is very thick,” he said. “I’ve never become a devotee because it creeped me out. Bhakti (the devotion yogic path) always annoyed the shit out of me. As a Westerner, I could never do that. I intellectually understand it, but I don’t emotionally or devotionally understand it.”

I told Kripal that I can understand the idea that, in a sense, we are all God, including Franklin Alpert Jones. We all have the capacity to experience a metaphysical, non-dual state of consciousness, to tap into a unitive “ultimate reality,” a higher power that we may experience as God. I’ve “seen the light,” but only with the powerful chemical assist that psychedelic drugs or sacred plant medicine can provide.

“So,” I asked the professor, “if we are all god, why do we need the guru?”

“Because we’re not aware of that,” he replied. “Why do you need LSD? You need LSD, or psilocybin, to give you an experience you otherwise wouldn’t have. The guru is essentially walking psilocybin or walking LSD.”

Kripal believes the spiritual power of the guru is not compromised by his sexual transgressions. It may even be part of the package. “Often this charisma goes with a kind of hyper sexuality. That’s another thing that people don’t want to hear. But it’s true. If you look at the history of religions, some of the most charismatic saints are also the most hyper-sexual, and often in very queer ways. Celibacy increases one’s sexuality; it doesn’t suppress it.”

We only get half the story, Kripal says, if we dismiss, condemn or cancel a guru because he seduces his devotees both spiritually and sexually. “This is the mistake we make in the West — that deification and spiritual genius has to somehow be moral or make you a nice person. That might be the ideal, but the historical fact is that it often does not…It’s the nature of charisma. It’s not socially safe.”

“Part of the problem with other gurus, like Swami Muktananda, was the denial and deception. In my correspondence with Adi Da, there was no nonsense about any of this. There was no denying his own sexuality… That’s one reason I so admired Ada Di. They were like, ‘Yeah. the guru has sex with his disciples.’ ”

Indeed. Those crafting the Adi Da legend do not deny that their guru had sex with female disciples in the 1970s and 1980s. How could they? A senior disciple who assumed a key leadership role in Adidam, Quandra Sukhapur Rani, openly writes about her sexual encounter with Free John in 1974, when she was a twenty-year-old devotee at the Lake County ashram. She approached him with a flower and bowed at his feet. Later in the day, she ran into him at the ashram bathhouse. “As He came in and sat down, I felt myself sinking into a deep trance state. I vividly recall Him just being there, giving me His Regard.” That night, she was invited to his house where “Beloved Adi Da took me through a series of profound Spiritual initiations.” But then, “almost instantaneously, He was my lover, and I was in love with Him. Our love was mutual, and, in this love-state, He embraced me sexually. I remained all night with my Beloved Guru, during which He initiated me into a Condition that I have never known before.”

Da Free John had at least three daughters born from liaisons like these back in the 1970s and 1980s. One of those children, Shawnee Free John, grew up to become an actress and model. Tamarind Free John works as a photographer in Southern California. Naamleela Free John, born in 1980, wound up doing her PhD work under Professor Kripal’s tutelage.

Her PhD thesis, completed in 2023, is described as “the first full-length scholarly study of the work of my father, Adi Da Samurai (1939-2008) — philosopher, artist, and founder of a twentieth-to twenty-first century new religious movement.” She sees her father’s work as “a compelling case study of East-West integrative spirituality…that lies at the very heart of American metaphysical religion.”

Naamleela Free John’s future role in this still-evolving religious movement has yet to be determined. Competing factions often emerge with the death of a cult leader, and Adidam is no exception.

“There are factions,” one insider told me. “Adi Da left several senior women disciples in charge. Many people consider Naamleela to be the most remarkable. She seems more like Adi Da than his other daughters. Some wish she could have a leadership role, but she doesn’t. There are factions, but one faction has no power. So we’re kind of stuck where we are.”

Georg Feurstein, a German/Canadian scholar who wrote extensively on mysticism and Hinduism, devotes a chapter to Da Free John in his book Holy Madness — The Shock Tactics and Radical Teachings of Crazy-Wise Adepts, Holy Fools, and Rascal Gurus (Paragon Press, 1991). In it he respects the guru’s early writings, but regrets that Free John and his followers have gone overboard in mythologizing the message.

Just months after my visit to his Fijian island, Free John had a mysterious “near death” experience that resulted in a particularly chaotic period. Five of his “nine wives,” including his legal wife and first devotee, were asked to leave the hermitage. “From then on he focused on working with the remaining four women renunciates, who are now reported to be in advanced spiritual states.”

Feurstein notes that Free John’s “sexual theater” of the 1970s and 1980s had lasting consequences. “Switching of partners, sexual orgies, the making of pornographic movies, and intensified sexual practices…led to the temporary, and in some cases permanent breakups of relationships…Some people were unable to handle the emotional roller coaster and left; a few still bear the wounds today.”

In Feurstein’s view, Free John’s messianic antics are more fascinating than illuminating. “They give one the impression of a quite extraordinary individual who, nonetheless, is overly preoccupied with his own evolutionary mystery.”

Feurstein, who died in 2012, saw Free John is “a born shape shifter, the proverbial protean man who is his own caricature.”

“He has acted as a loving friend, a belligerent madman, a boisterous clown, a sorrow-stricken individual, a smitten and jealous lover, a preemptory king, a remorseful confessor, an oracle of doom, an arrogant dilettante, a drunken with slurred speech, an inspired poet filled with wonder, a proud father, a stern disciplinarian, an incorrigible imp, a solemn sage, an uplifting minstrel, a sexual obsessive, a perceptive philosopher, a childlike person, a decisive businessman, a frail mystic, a tormented writer, a tireless preacher, a man of immeasurable faith and confidence, a ruthless critic, a wiseguy, an enlightened beast…”

(Thanks for sticking with me, dear readers. That was a long one. Next week we will radically shift gears to another messianic madman — Donald J. Trump. Please subscribe to “Messiahs I Have Known” on Substack, if you have not done so already.)

This was a terrific piece Don. I loved seeing your back and forth with Jeff and I’m sharing with my colleague who teaches our cults and sects course.

Your final saga with Adi Da was a masterful reversal—what in hockey terms would be called beyond the hat trick. It’s heartening to see how you’ve opened up the realms of enlightened possibilities.